🦊 Write It While It's Hot

#83 — Striking while inspiration is hot, semi-public sharing, and the struggles of maintaining momentum.

Yesterday, Michael Nielsen published a fascinating note on creative contexts. He cautioned that his note was rough and written quickly, but it was filled with insights that resonated deeply. It inspired me to switch gears on today’s newsletter, and devote the afternoon to writing a rough newsletter about the powerful ideas in Michael’s note.

Ready to play rough with ideas? Read on!

Firstly, what are creative contexts? Michael’s note focuses on what he describes as “narrow creative contexts.” He contrasts them from the physical creative environments often discussed:

There's a huge amount written about creative environments: from Bauhaus to Bloomsbury to Renaissance Florence to how to set up a modern research group or company or artist's colony or writer's workshop. I'll call those broad creative contexts.

But my focus here is on something I've seen much less discussed, what I shall call narrow creative contexts (mostly omitting "narrow"). This is the tiny little nub of a thing – maybe just an image or a phrase – that you hold onto, that gradually comes into focus, and then blossoms, the animating force driving the project. It's the emotional and intellectual force driving the work, the thing you return to over and over.

I think of Michael’s description of a narrow creative context as the internal spark that fuels a creative project. We decorate our desk with special memorabilia to inspire us in times of need, so perhaps we can do the same with our ideas. Creative contexts can be the inspirational furniture in the workspace of our mind.

The specific examples Michael shared are enlightening (below is a subset of the full list Michael shared):

That email message that really pisses you off;

That connection you see, that demands to be elucidated;

The thing someone said in a talk that made you overflow with ideas, or enjoyment, or irritation, or […];

The thing you’re scared might be true;

The thing everyone in your community believes, but which you know is wrong;

I recognized many of these examples as the sparks behind my own creative works. These serve as driving forces for big projects (like a book), as well as small projects (like a newsletter or essay.)

With a heightened awareness of these “sparks,” I wondered: How can I make the most of them?

Delay is Decay

I often think about the delicate nature of ideas, and how Steve Jobs framed them (Michael references this very quote): “they begin as fragile, barely formed thoughts, so easily missed, so easily compromised, so easily just squished." Jobs was alluding to the importance of a welcoming environment for ideation—people need to be open rather than dismissive to let ideas blossom.

But even in the context of solo work, there is a great threat to our ideas: Time.

The energy of an idea is time-sensitive. It arrives bright as the sun, but its radioactive nature means it decays over time. We have to make the most of the light while it still shines.

When an idea strikes, it’s tempting to just write a private note (usually a bulleted outline) to come back to later. This is a great first step, but it’s risky to stop there! When you abandon it so early, it leaves the idea in a vulnerable state.

Every writer has seen this scenario before: You have an idea. You excitedly write some outlines, using wording that makes sense to you in that moment. You go on with your life, and plan to come back to it. You don’t. Weeks or months later, you look at the note and wonder, “What is this about? And who cares about it?” The answer to the latter question is not you, but a past version of you.

If you’re lucky, a future spark may revive it. But in all likelihood, once you wait, it becomes too late. Your interests shift quickly. It’s almost impossible to write a great piece about something you don’t care about. (If you try to force it, readers will notice. A writer’s energy—or lack thereof—is revealed in every word.)

Not every idea needs to be shared. But when I’m gripped by an idea, I do my best to write something about it quickly, before its energy fades.

As often as possible, I try to write it while it’s hot.

To play devil’s advocate: What about the ideas that need time to simmer? Sometimes we can put an idea aside and come back to it with a new lens—a refreshed perspective that we didn’t have before. Even in those cases, I’d argue that a short published piece is far more useful than an unpublished outline.

The clarifying work of early expression eases the task of future connection.

Semi-Public Sharing

The main reason it’s so tempting to keep things private is that publishing can be scary. We fear the full range of responses from the terrifying trolls to sobering silence.

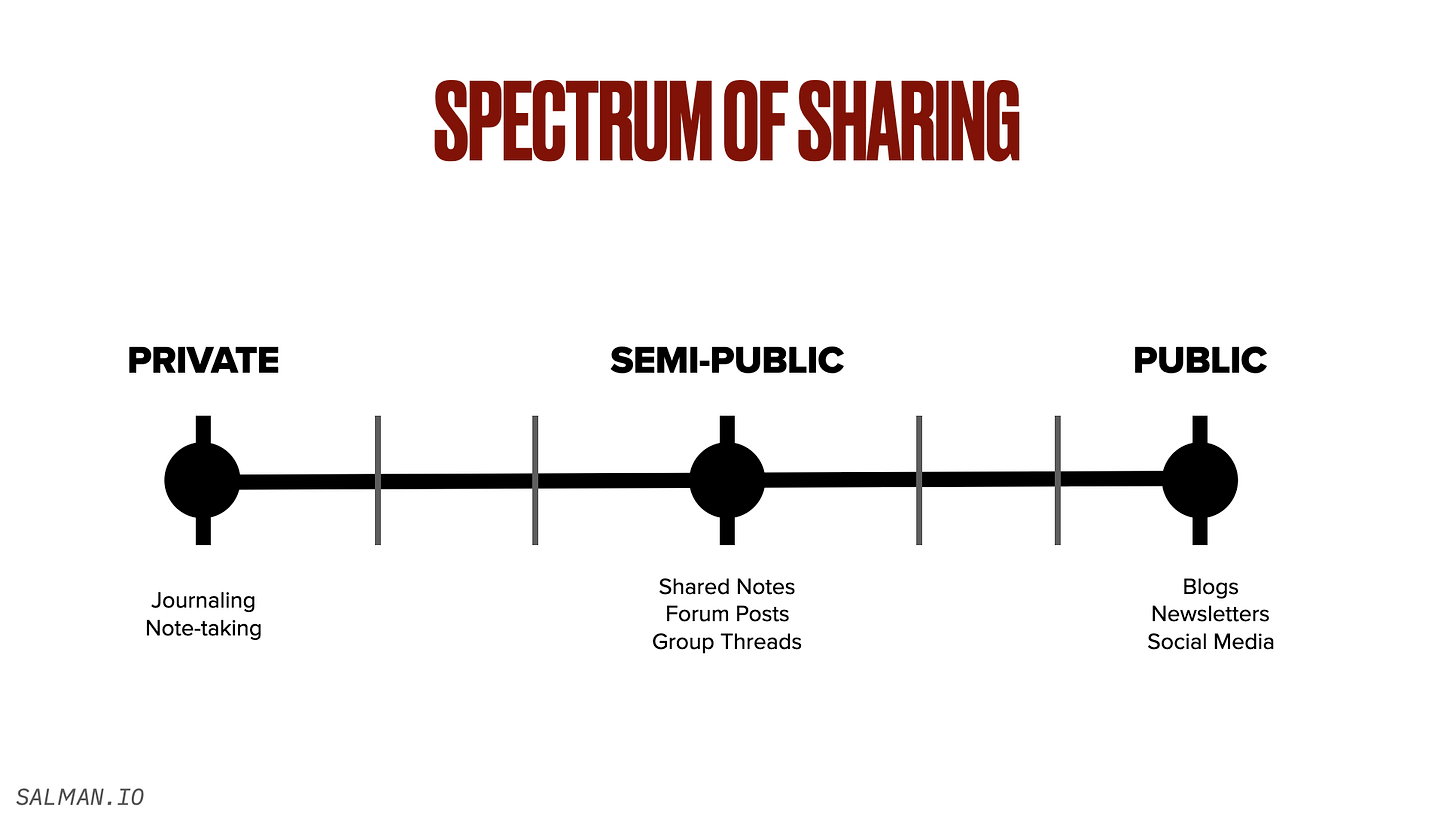

It doesn’t have to be so scary. We don’t have to expose every idea to the vastness of the internet. We can mitigate the risk through “semi-public sharing.” I explored this approach in an earlier essay, Low Stakes, Strong Takes:

To share your work semi-publicly, start by ensuring it’s accessible with a URL. You can use your own website or tools like Google Docs or Notion to host it.

Avoid posting it on social media. Instead, share links to your work freely with trusted peers through text messages, emails, DMs, and so on. This way, you benefit from the convenience of easily sharing links with your peers, while still knowing who has access to it. When you share with a trusted group, it elevates your willingness to express what you really want to say.

By controlling visibility, you unlock vulnerability.

In his note, Michael mentions his own approach of shipping his work through different channels, ranging from WhatsApp messages to rough notes on his notebook (including the note that sparked this letter!) He emphasizes how limiting the audience can clarify the message, too:

It may only be for a tiny few other people, sometimes just a single person! But having extreme clarity about who am I making it for, and why, often helps enormously.

Limit your audience to liberate your ideas.

The Price of a Pause

Another bit that resonated strongly was Michael’s points on the risk of breaks:

They take a break for a day or two, and boom, they're out of it. And absent someone else to help them get back in, it can be hard to get back into it!

I’ve been writing my book of fables for over a year now, and one of the things I’ve noticed is how easy it is to lose momentum. If I skip working on the book for a day, it quickly turns into two, and before I know it, I haven’t made traction for over a week, sometimes more. The longer I delay, the harder it is to get back into it. It becomes exponentially expensive to resume.

Michael notes that the cost of a break is a primary reason why creative people often work “monomaniacally” on things:

Stephen King says he never takes a day off writing, including Christmas and birthdays. His advice to other writers: do the same. Or, if you can’t do that, have at most one day off per week. I don’t think it’s because he’s a workaholic, or because he couldn’t stand a 14 percent decrease in productivity. It’s because he fears one day a week off would lead to more like a 50 (or 100) percent decrease in how much he writes, and maybe an even larger decline in quality.

Given the risks of losing momentum, one could argue it makes the most sense for me to show up and work on my book, day after day without exception. But past experiences with overwork and startup burnout have made me very careful about these kinds of commitments. I’m slowly rediscovering my drive and ambition after struggles with burnout. If I want to avoid the traps of the past, I have to be mindful of how I take my steps in the present.

Finding the right balance is a tricky thing to navigate.

Over time, I’ve come to realize that my personal creative projects have a different feel than the startup projects of my past. Personal projects are far richer in terms of intrinsic motivation, so there’s less risk of burnout. (Burnout tends to happen most when you overwork and don’t have a strong why behind the work.) I gain a lot of joy from these solo projects, and I really believe in their vision. Moving too far from them is actually a painful thing. As Liz Gilbert said, “Any talent, wisdom or insight you have that you don’t share becomes pain.”

Luckily, I’ve found that I don’t have to show up for a marathon session every day. I can show up for just fifteen minutes, and that can be enough. In this way, I lighten the load of the commitment, which limits the risk of burnout. As a result, the project becomes more sustainable in the long-term. In a prior letter, Showing Up, I wrote about how taking small steps every day helped me write my book:

If we ask ourselves to take just one step, the mountain becomes manageable. When we’re standing still, a single step is a giant leap.

At the end of Michael’s note, he mentions feeling a bit odd writing so much about solo creative contexts. “It feels silly to talk about,” he wrote. I tend to write a lot about creative process, so I didn’t quite feel the same way writing this newsletter as he did writing his note. But I can understand why he felt that way—typically in group projects, much of the concerns discussed here are addressed automatically (by group process and/or by leadership.) Most contributors to the project can take this stuff for granted. The burden of keeping you motivated about the project usually falls on someone else’s shoulders.

By contrast, solo projects demand that you figure all this stuff out yourself, and implement it effectively enough to keep you going. I’ve often felt that once you quit your full-time job to go independent, managing yourself becomes your new full-time job.

But the unique challenge of solo projects is also what makes their output unique. As Michael noted, “it enables certain kinds of work that I don't think can be done in any other way.”

If I want to take on ambitious solo projects, then I need to engage in this “meta-work.” I must understand my own relationship with creativity, and ensure that the steps I’m taking are effective, enjoyable and sustainable.

To do my best creative work, I must embrace the meta-work.

I’m grateful to Michael for generously sharing his ideas and publishing his note. It gifted me with the creative context to write this newsletter. (You can follow more of Michael’s work on Twitter @michael_nielsen and his website michaelnielson.org.)

Love this. I often find delay is decay... up to a certain point. I write as much as I can as soon as I have an idea, but eventually I arrive at a point where I don’t know what comes next, or where there’s a hole in the story. Then I have to step back and chew on it, think about what comes next. I’ve been chewing on one particular hole in a story for almost a year now, but I think about it everyday. I have the timeline for the novel in my office, and a picture on my fridge that represents the story. It keeps it fresh in my mind!

Great article. When an idea comes to me when I'm trying to sleep I always tell myself that I'll hold onto it, that I'll remember it in the morning, but it has always either gone or it has lost its vibrancy, so this idea that ideas have a short half life resonates with me.

All day yesterday I had two "seeds" floating around my head but no means to capture them. When I did finally get back to my notebook, one was caught, the other just drifted away on the wind. If I didn't know more ideas were around the corner I'd probably find this a bit depressing